I too had the pleasure of receiving an invitation to the amusingly titled ‘Big R’s’ and enjoyed excellent company and conversation. Jack Chew and colleagues are to be commended for hosting the event with Connect Health with a proposition to “Reason” with “Responsibility” and the idea of “Reforming” musculoskeletal practice. Connect Health should also be congratulated for putting forwards their values, strategic goals and aspirations in such an open environment. It is in the spirit of the three ‘R’s that I would like to focus on a common theme throughout the evening that has been touched upon by Neil earlier with respect to knowledge translation.

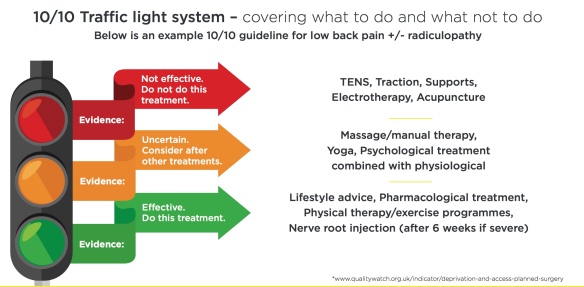

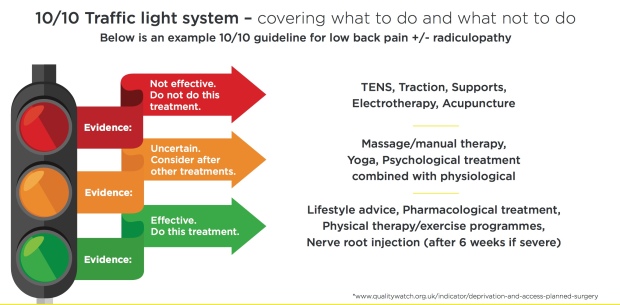

Connect Health, put forward, as part of their “10/10 MSK Guidelines” (http://www.connecthealth.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Connect-Health-10-out-of-10-Infographic.pdf) for improving efficiency, reducing clinical variation and improving clinical outcomes, a traffic light system that stipulates the appropriate treatment interventions according to each presenting condition. The justification for the traffic light system is emboldened by a speech bubble that reads:

“If you read one article per day, you’d be 20 years behind, so we needed to close this gap and help our clinicians have evidence at (sic) finger tips”.

This suggests that the traffic light system provides a solution to knowledge translation between ‘evidence’ and practice.

I would like to attempt to unpack some of the challenges surrounding knowledge translation and the use of a traffic light system. The traffic light system appears to convey a linear and non-value laden indicator of efficacy. They categorise ‘evidence’ into red (ineffective treatment indicating that clinicians should not do this intervention), amber (uncertain, consider after other treatment interventions) and green (effective, do this treatment) lights. At first glance, this may seem a reasonable, simple and effective method. Let’s take a closer look, first of all, what is knowledge?

Aristotle described three main aspects to the concept of knowledge. They are episteme, techne and phronesis:

- Episteme means, “to know” in Greek. It represents knowledge as ‘facts’ and Plato contrasted this with ‘doxa’which meant common belief or opinion. For example, a therapist may need ‘to know’ many areas of human biology in order to understand how exercise can be utilised as an intervention to treat back pain or to prevent cardiovascular disease.

- Techne translated from Greek means craftsmanship or skill. It draws from knowledge but is situated in the skill of its delivery. For example, a therapist may be knowledgeable in the theory of motivational interviewing but struggles with the skill of its delivery. Techne also includes tacit(understood or implied without being stated) knowledge. Tacit knowledge is embodied, sub-conscious and embedded to personal experience and is the type of knowledge that is very difficult to record or write down. For example, emotional intelligence, communication skills, leadership skills and clinical intuition are commonly cited in healthcare research and practice but are very difficult to conceive or teach.

- Phronesis means practical wisdom. It relates to the ethical deliberation of values with reference to practice. It is related to praxis in that it refers to an action that embodies a commitment to human well being, the search for truth and respect for others. It requires that a person make a wise and prudent practical judgement about how to act in this situation (Carr and Kemmis, 1986: 190).

These aspects of knowledge described by Aristotle form an individual’s knowledge. Now, referencing back to the traffic light system. Immediately, you can see that the traffic light system delivers one of the aspects of knowledge, namely episteme, but provides little or no reference to techne or phronesis. Its creator(s) must have made this synthesis of ‘evidence’ with some value judgement as to what good evidence is and is not, but it is not clear how this judgement has been made. One assumes that this judgement was based on an evidence-based hierarchy but it does beg the following questions. Who created the judgements? To whom does their purpose serve, the patient, a population, the therapist(s), the organisation or all of them, and in what way? Does it achieve those aims and at what cost? What values are being accounted for (clinical outcome, financial, quality of life of patients, therapist understanding)? What judgements are made in order to delineate an amber intervention as opposed to a green or red intervention? For example, Pharmacology treatment is cited within the low back pain +/- radiculopathy traffic light system as a “green light”. This is despite pharmacological studies evaluating paracetamol being ineffective for spinal pain and osteoarthritis (Machedo et al, 2015) (http://www.bmj.com/content/350/bmj.h1225), NSAID’s not showing clinically important difference against placebo for spinal pain (Machedo et al, 2017) (http://ard.bmj.com/content/76/7/1269) and Pregabalin not being effective for moderate to severe sciatica (Machieeson et al, 2017) (http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1614292?rss=searchAndBrowse#t=article) amongst other examples. Clearly, the context may be of utmost importance here such as the stage of the disorder, presentation, co-morbidities, and presence of barriers to recovery, previous response to treatment amongst a dearth of other relevant information. The question remains, is the underlying context revealed using the traffic light system?

Creating a hierarchy of evidence is in itself is fraught with problems and challenges. Further discussion of these challenges are beyond the scope of this blog and the literature is extensive but I would encourage readers to watch Trish Greenhalgh speaking about ‘Real verses Rubbish EBM’ here (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qYvdhA697jI) and work from Roger Kerry (http://www.mskscienceandpractice.com/article/S2468-7812(17)30153-4/fulltext) as well as work from the CauseHealth team (https://causehealthblog.wordpress.com) (https://philpapers.org/archive/ANJD.pdf) (http://ubplj.org/index.php/ejpch/article/viewFile/1129/1129) and also the Alliance for Useful Evidence (http://www.alliance4usefulevidence.org/assets/What-Counts-as-Good-Evidence-WEB.pdf).

Knowledge does not exist in isolation but exists within a social context. An exchange of knowledge occurs through shared cultural understanding, practices and assumptions and not by a mere exchange of factual information. The traffic light system appears to specify an absolute system of context-free judgements on clinical practice regardless of individual and environmental factors. For example, the abandonment of the use of therapeutic ultrasound was posited as a “good place to start” when reforming MSK practice. However, experts in electrotherapy such as Professor Tim Watson are likely to hold exception to such rules as the evidence demonstrates efficacy if sufficient treatment dose, within the context of an appropriate tissue injury and healing stage, has been provided (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hpMFI7UPwMo). Interestingly enough, this is the same as many other treatment interventions in Physiotherapy, including, dare I say it, exercise! A more appropriate suggestion might be that therapeutic ultrasound should not be justified in areas of practice where environmental and practical elements prohibit its efficacy, e.g. using therapeutic ultrasound in a sub-acute muscle tear once every two weeks. As a potential consequence of using a broad brush-stroke approach of describing all therapeutic ultrasound as lacking in sufficient evidence, and therefore abandon its use, is very likely to polarise the MSK community rather than bring it together in a reform of practice, particularly bereft of context. (P.S I would like to declare that I do not use therapeutic ultrasound in my practice, as I do not see the appropriate caseload or work in an environment that would constitute its effective delivery).

Perhaps polarising views could be a way to draw people into a debate or discussion and perhaps this could be the right thing to do? But, I can’t help but think that this approach might be rather disengaging and autocratic, using evidence as a proverbial stick to beat you over the head with. It might be seen that organisations could try to ‘kitemark’ what is good evidence and drag the MSK community of practice “up with it”. However, I can not avoid the feeling that a close relationship exists between knowledge and power with evidence being described as “what powerful people say it is” and, that in its pursuit, could lead onto stifling significant change in practice rather than foster and grow it (http://www.ruru.ac.uk/newsevents.html). Indeed, creating policies without broader considerations could be seen as using rhetoric to achieve the goals of an organisation with an undertone of efficiency making, cost-cutting, money saving and the handcuffing of professional autonomy.

Gabbay and Le May (2011) describe ‘clinical mindlines’ that go far beyond guidelines as “internalised, collectively reinforced and often tacit guidelines that are informed by clinicians’ training, by their own and others clinical experience, by their interactions with their role sets, by their role sets, by their reading, by the way that they have learnt to handle the conflicting demands, by their understanding of local circumstances and systems and by a host of other systems” (Gabay and Le May, 2011 p 44). One could look at the social media explosion surrounding the big R’s event as well as Physiotherapy continued professional development over the last five years and see it in a way that builds clinical mindlines, but perhaps with some unforeseen consequences. Less experienced therapists that seek knowledge through social media may experience a gold mine, full of forward thinking and verbose well-meaning healthcare professionals. What in actual fact, they might receive is ‘doxa’ or common opinion without much critical thinking surrounding such information. All the more reason for open discussion, deliberation and debate!

The vision of providing a system that values reducing clinical variation is both compelling but also concerning. Allowing clinical reflexivity and context-dependent, autonomous decision-making should be rewarded and at the same time ensuring effective clinical reasoned interventions. Is this process one in which is embodied with a traffic light system of intervention that appears to rewards technicians and not skilled practitioners?

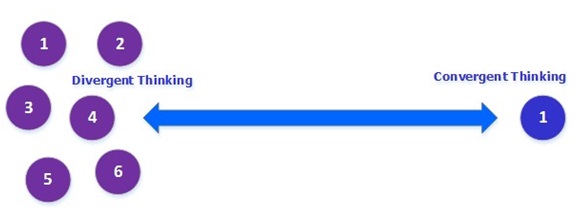

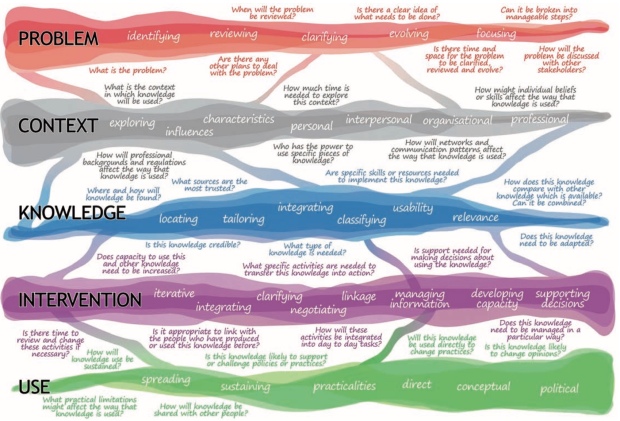

Knowledge translation is a complex, dynamic and reflexive process and might best be viewed like this:

Dr Vicky Ward, Dr Simon Smith, Dr Samantha Carruthers, Dr Susan Hamer, Professor Allan House (2010) Accessed 19/11/2017 18:52 http://medhealth.leeds.ac.uk/info/662/kt_framework/774/project_report_and_publications

This is quite a contrast to the traffic light system and is food for thought in comparison. However, the traffic light system is a start, especially for newly qualified therapists using it as a heuristic for guiding clinical practice. Clearly, this blog asks more questions than it does answer any, but I have tried to put forward some suggestions that might be helpful.

- Providing an open and transparent process for judging clinical guidance.

- Acknowledge one’s own clinical practice, research assumptions, values, judgements and beliefs as our ‘facts’ are always value-laden.

- Provide a framework for understanding and signpost where the gaps of our knowledge are and promote reflective practice.

- Be open regarding our aspirations for the future, which may provide opportunities to use evidence in a more informed and reflexive way.

- Encourage clinical mindlines by discussion, debate and use the application of multiple sources of ‘evidence’ at the same time as acknowledging the limitations of the methods from which they came.

I would also like to add Roger Kerry’s key messages from his recent paper ‘Expanding our perspectives on research in musculoskeletal science and practice’ in the Musculoskeletal Science and Practice journal as they are very relevant (http://www.mskscienceandpractice.com/article/S2468-7812(17)30153-4/pdf).

- Clinical practice should be based on best evidence, and an era of “clinical freedom” should not be returned to.

- As scientific research exponentially grows within musculoskeletal medicine, it is timely to re-examine what constitutes the best evidence for clinical decision making and health policy.

- Traditional scientific principles on which much existing research is based are dated and limited by real-world complexity, and a crisis period in both research and practice is now evident.

- A research vision for the future is focused on knowledge generation which is truly person-centred and embraces real-world complexity, rather than controlling for it.

- The research future should incorporate greater alliances between all stakeholders and expand its context and theories.

- Clinicians, researchers, and the people we work with to improve their health should continue to reconceptualise the idea of best evidence for clinical decision-making and health policy.

Results

Results